The Psychology of Waiting

People don’t like to wait.

When it comes to web browsing, it’s been proven numerous times that a slow website annoys us. For users to have an enjoyable experience, the recommended practice for a website is to load between 1-2 seconds, but why does it need to load quickly? What’s the human explanation behind it?

In this post, I want to take a step back and explore the reasons why waiting could be an unenjoyable activity and give you an overview of the following:

- The two angles of waiting and the psychology of how waiting works

- Why waiting on the web matters

- Tips on optimising the psychology of wait time and improving UX even if you can’t necessarily do things faster.

The two angles of waiting

Have you ever waited in a queue while you were at the supermarket and often felt like you chose the wrong line because the other line moved faster? This was me just a couple of days ago when I had to buy a few items from my nearest supermarket. I tend to listen to music or put on a podcast to occupy my thoughts, but this particular day I had forgotten to charge my AirPods. Having no music or podcast to distract me, I was left with no choice but to experience boredom while waiting, and I hate to admit it, but it wasn’t a fun experience, mainly because I only had to pay for four items.

There are, of course, moments where I don’t mind waiting, like queuing up to watch a concert or being seated at a restaurant I want to try. These moments are often accompanied by excitement, and I know it’ll be worth the wait. My experience while waiting for these experiences leads to my perception of time, and this is different from the objective measure of time.

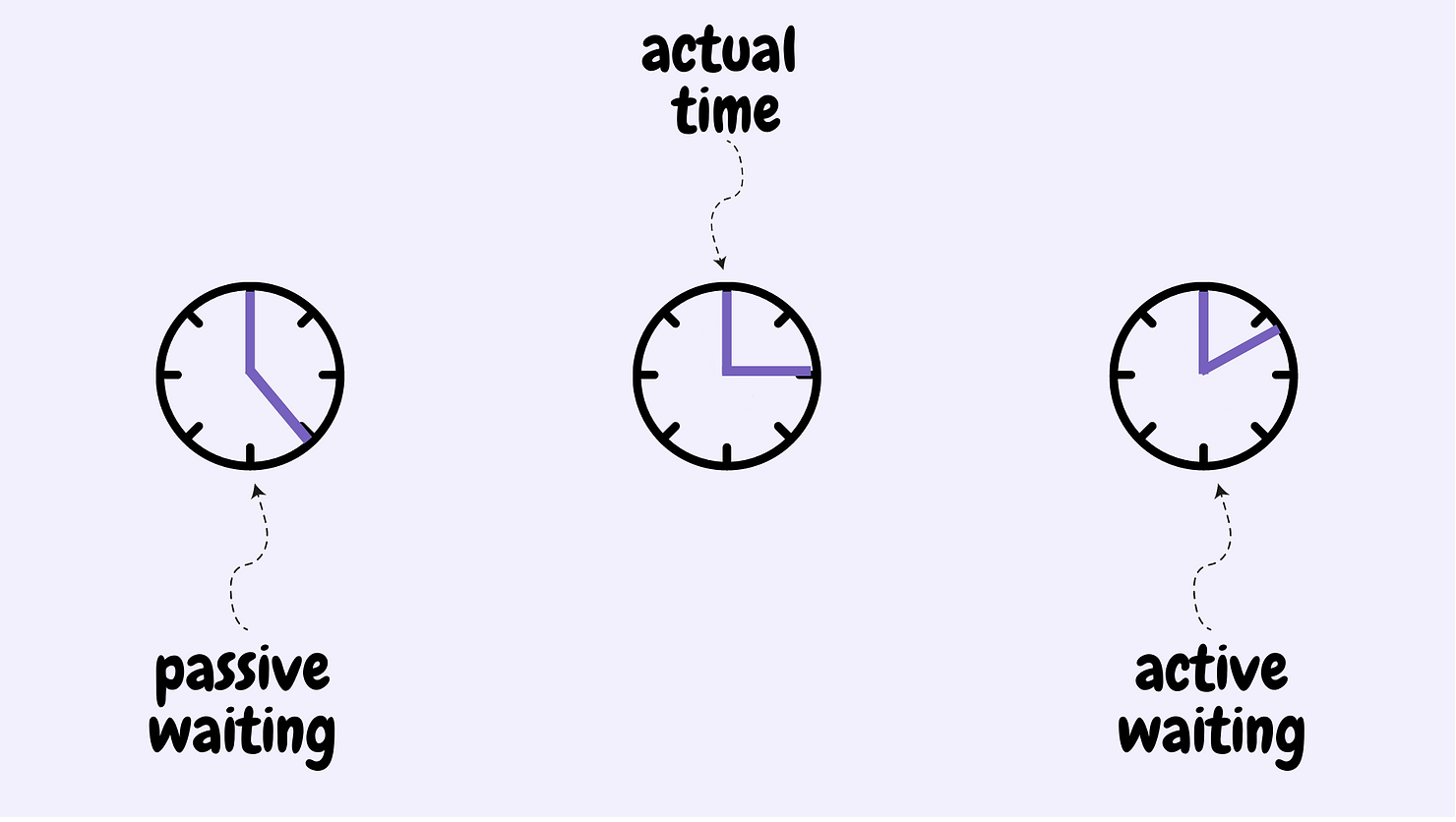

This is because time can be measured from two different angles:

- Objective

- Psychological

When we look at time objectively, we think of the actual time measurement in seconds, minutes, or hours.

However, the way we perceive time is different from the objective time. From a psychological angle, we think of waiting in two phases. There’s the active waiting and the passive waiting. Active waiting occurs when we are engaged in an activity, so we often lose track of time.

On the other hand, passive waiting is when we don’t have control over the waiting time. When we are in the passive phase, we know that time is moving slowly because we are bored. This would explain why waiting at a supermarket feels longer to me than waiting in line to go to a concert.

The Psychology of Waiting

Last year, I stumbled upon an article that David Maister wrote called The Psychology of Waiting Lines. If you have not had a chance to read this article yet, I urge you to do so. David was widely acknowledged as one of the world’s leading authorities in managing professional service firms. As part of this article, he talked about various human explanations for why waiting is not enjoyable, especially if we are in a passive state.

Let’s explore these different explanations one by one.

Occupied time feels shorter than unoccupied time

Do you often feel that waiting for your food to be microwaved feels longer than expected? This happens when you actively wait rather than engage in other activities. When I microwave my food, I occupy my time by doing something else, such as washing the dishes or making a cup of tea. It’s funny how many things you can sometimes accomplish while you wait for the microwave to finish.

People want to get started

We are impatient creatures. It’s just our human nature. A great example of this is eating at restaurants. When we get seated quickly, we feel that the service has started already, even though waiting for the food might take longer.

Anxiety makes waits seem longer

Have you ever taken a 5-year-old to have their vaccination done? I have, and my experiences have been different for both. The first time she had her Covid vaccine, she was wonderful because she was given colouring pens and papers to keep herself distracted. The second time, her anxiety was much higher because there were no activities to keep her distracted. She had to face the waiting while being aware of what was happening. Keeping someone’s anxiety down makes a massive difference while waiting.

Uncertain waits are longer than known waits

If you’re not being told exactly how long you have to wait, your expectation is not being managed, and the waiting feels longer, which also correlates to higher anxiety. For example, you get irritated more when there are train delays but no indication of how long the delay will be. However, if a time is added next to it when the next train is most likely to come, you accept the delay better.

Unexplained waits are longer than explained waits

If someone asks you to wait without any clear explanation, this uncertainty makes the wait unenjoyable. By giving a human explanation as to why the delay is happening, users can accept this better. Imagine if you are waiting at an airport and no one is informing you why the flight is taking longer than it should. Can you imagine how many agitated flyers there will be?

Unfair waits are longer than equitable waits

A frustrating experience in the physical world is if you’re waiting in a queue to eat at a restaurant. Still, some people who arrive later are given priority seating which causes you to become agitated. Or, if you’re trying to get on a busy train, but the person behind you pushes in, you end up not getting in after waiting for too long. This feeling of being agitated makes the waiting experience horrible.

The more valuable the service, the longer the customer will wait

This explains why I don’t have problems waiting in line to see a concert or waiting to be served at high-end restaurants. I know the service will be more valuable, so it’s acceptable to wait a bit longer. On the other hand, if I’m told that I need to wait 45 minutes to get something to eat at a fast food restaurant, my experience of waiting will come across as unfavorable.

Solo waits feel longer than group waits

The final explanation is that solo waits feel longer. When you’re standing in line alone, waiting for feels longer than staying in a group. This is because when we are more engaged, the less we notice the waiting time.

Waiting on the web

When it comes to waiting on the web, the speed of your website matters, Jacob Nielsen stated that 1.0 seconds is the limit for the user’s flow of thought to stay uninterrupted in his article, Response Time: The 3 Important Limits.

Making performance improvements to improve the objective performance is important, but further enhancements should also be made to improve the perceived performance, leading to a much better user experience.

I’m not a UX expert or anything like that, but from my experience working with teams that specifically improve a website’s performance, here are some recommendations that can help improve the perceived performance of your websites:

Show something fast

Slack displays a skeleton framework to show users that something is loading. A skeleton gives you a preview of what you’re about to see. This way, the users feel occupied while they wait for the API calls to complete. If users stare at a blank screen, users will go to the passive mode of waiting and end up frustrated.

Similarly, when users visit a web page, it’s much better to display something fast when it arrives, whether it’s the text or a logo, than wait for all other content and resources to load. This way, the user can see something is happening quickly and feel that their experience has started.

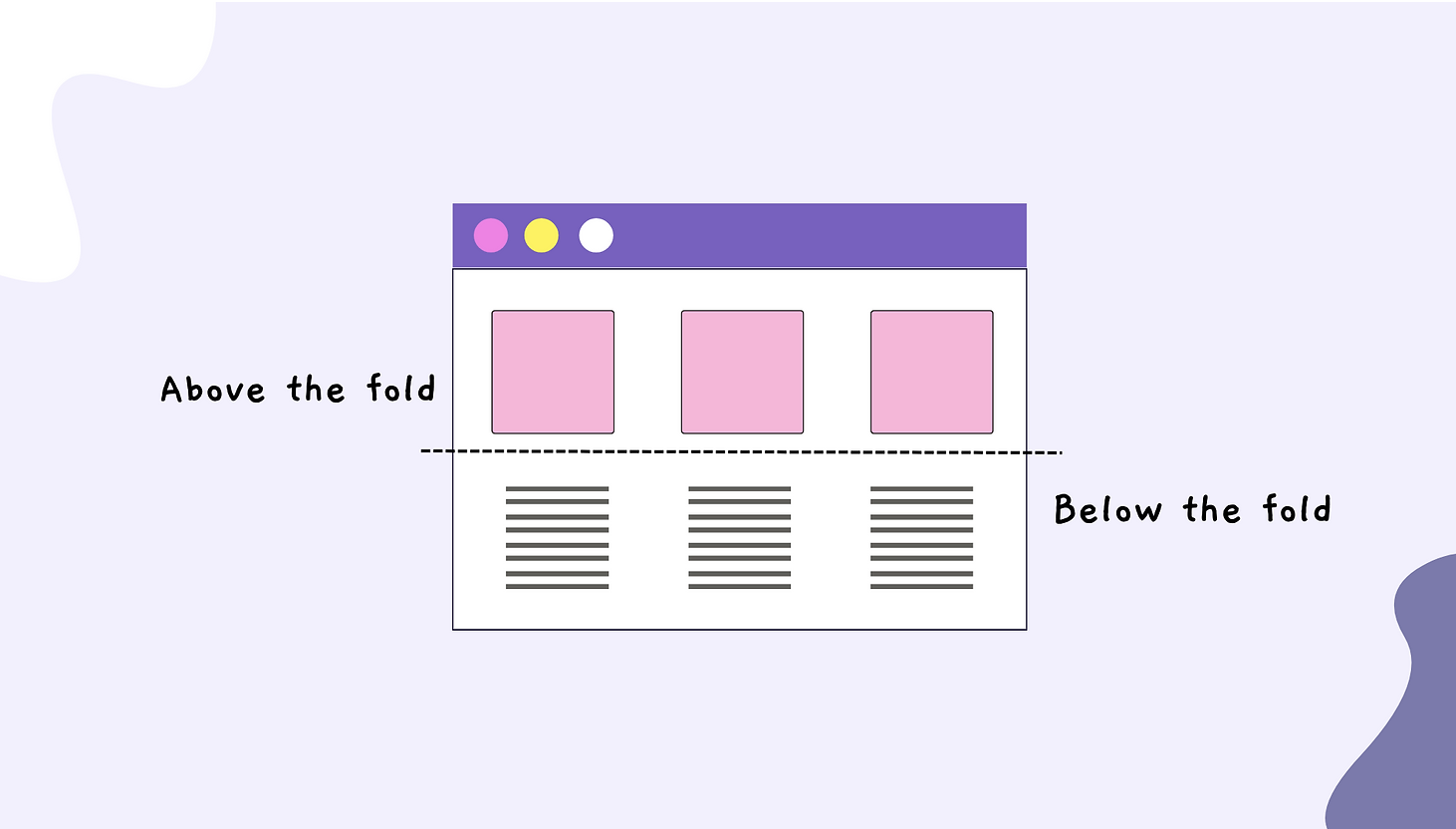

Load above-the-fold content first

The content found above the fold is what your users visually see immediately when they visit your website without scrolling down. Since this is what they see for the first time, critical content should be placed above the fold, so it’s displayed immediately. Remember the saying, “the first impression is the last impression.”

For example, if you have a news website, loading the headlines is critical because the readers can instantly know what they are about to read. If it’s loading slowly and the information they want is not displayed immediately, the bounce rate will be higher, and they’ll go to a different news website.

Lazyloading

Lazyloading is another technique for improving the perceived performance of your website. With lazy loading, you load the resources when it’s needed. A great example is from the Medium website, where a low-quality image is loaded to reduce the initial page load, and it’s then replaced with the actual print once the user scrolled down to it.

Look out for the visual stability of your pages

When resources such as images, adverts, videos, or any DOM elements are loaded asynchronously, this can cause unexpected movements to your website, which can get annoying. In some severe cases, this can impact your users negatively. A vital core web metric you should track is the Cumulative Layout Shift (CLS).

CLS is a critical, user-centric metric for measuring visual stability because it helps quantify how often users experience unexpected layout shifts.

Provide feedback regularly by showing progress indicators

In Grafana Cloud k6, when you run a test, the setup stage also takes some time, especially if you want to run a high number of virtual users. To occupy the user’s time, we show animations and provide valuable messages to let the users know something is happening. Imagine if the messages and animations are replaced with an endless loading spinner. You won’t be able to tell if it’s still processing your request or if there’s an actual issue with the page or your internet connection.

By also giving a human explanation as to why the wait is happening, your users can accept this better.

The importance of perceived performance

Regarding web performance, it’s common for us to make improvements to make our pages load faster. These improvements are all valuable. However, it’s also essential to understand the psychology behind waiting, the human reasons why people don’t like to wait, and how our perception of performance is not the same as the actual performance.

By employing additional guidelines to make your website feel fast to users, you’re ultimately improving their user experience.